Over three days in June, the Second Parliamentary Conference in Interfaith Dialogue convened in Rome. Three scholars from the Cambridge Interfaith Research Forum attended:

Dr Ayesha Ulhaq [AU], whose newly-minted PhD documents the emotional geography of British Muslim women; Dr Marietta van der Tol [MvdT], whose latest book documents intolerance in constitutional law across Europe; and Dr Vanessa Paloma Elbaz [VPE], a musicologist whose work records patterns of intercultural encounter between Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Western Mediterranean.

CIP partnerships lead Dr Iona Hine [IH] caught up with them post-conference to learn about the experience.

IH: Let's begin by explaining how the three of you came to be in this context. I think you all learned of this opportunity because we included it among last term’s Research Forum notices, with the mention that we had earmarked some funding to support someone to attend. What attracted you to participate?

AU: What attracted me to this opportunity was the chance to attend an event that brought together interfaith dialogue, policymaking, and global perspectives on areas such as religious expression, freedom and the impact of religious dialogue/practices on communities — all areas that align closely with both my academic work and personal interests.

I recently completed my PhD on Muslim women's experiences of safety and trauma in Britain, and I’ve since become increasingly active with the Cambridge Interfaith Forum. That space has deepened my interest in interfaith work and has also made me reflect on the intersections between religion, politics, and lived experience. I also come from a policy background, having worked as a civil servant, so this event felt like a unique opportunity to bring together the academic, civic, and faith-based aspects of my work. It seemed like the kind of space where I could both contribute to and learn from ongoing global conversations.

VPE: I was very interested in participating for various reasons. One was because the first iteration was in Marrakesh, and was led in part by the Rabita des Oulemas whose director Dr Abbadi I have known for many years. I have been participating in and researching the interfaith work that Morocco has been doing in the last two decades. To see how what they had launched was taking on a life of its own, inspired by the familiar interfaith propositions they are putting forth, was very interesting.

Additionally, the opportunity to speak with policymakers and see how they are facing the crisis we are facing in our day was an utmost priority for me. Most often cultural actors are not part of these conversations as they are left to political experts, theologians and economists, but culture is one of the focal points that can allow for non-confrontational understanding through getting to know the inner world of the other. I wanted to start having this conversation with some of the parliamentarians.

MvdT: Parliaments play a significant role in the way laws are formed that affect ethnic and religious minorities. I was interested to see the way in which different delegations speak about the fundamental rights of minorities, and how they respond to each other when particular interests clash. For example, how does a country that represses a particular minority call for the protection of their compatriots who live as minorities in other countries? Or how do representatives respond when their country is called out for the violation of certain fundamental rights?

IH: Let's turn to what this experience was like in practice. The setting is constructed as a “Parliament”. Was that mode of operation familiar to you? How does such a structure enable and or inhibit interactions?

AU: The parliamentary setting was quite new to me. While I’ve worked in policy before as a civil servant, I hadn’t been in such a formal parliamentary structure, particularly at the international level. What struck me was how the setting gave the dialogue a sense of seriousness and visibility. It also enabled a wide range of interactions between parliamentarians, religious leaders, scholars, and civil society representatives—all within a shared space.

The structure lent itself well to cross-border relationship-building and gave attendees a chance to hear directly from senior figures about how policy and faith intersect globally. For me, it was also a rare opportunity to see how senior leadership figures approach dialogue, and how such structures can be used to legitimise and platform marginalised perspectives—though that wasn’t always consistent.

VPE: I had not been at a Parliamentary proceedings previously, but had been within international parliamentarians at COP 22 in Marrakesh (2016), so was familiar with the informal channels within which they interact with each other. However, the formality, and public aspect was interesting, as well as the crafted messages that each representative presented, in manners that often seemed performative and even on occasion insincere.

The leadership of the IPU was clear in their desire to hear all voices and to hope for actions coming from the meeting, albeit also privately stating frustration that not much action or change has been seen since the first meeting. I was interested in comparing the public-facing statements with those in off-the-record conversations—it was being able to see this dichotomy and the continued presence by the leadership in encouraging dialogue leading to actionable decisions that made being there immensely valuable as a manner of understanding how to enact some form of effective communication as an academic going forward.

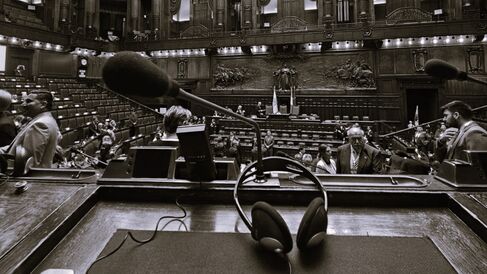

MvdT: For my book Constitutional Intolerance, I have studied Parliamentary processes behind major laws that impact on religious freedom in several different European countries. I’ve also listened to livestreams of Parliamentary debates, when such laws were actively being debated. It’s still different to be “in” a Parliament and observe the routine and liturgy of Parliamentary movements. The space, the people, the layout of the room, the art, the lighting—it all shapes the space in which debates happen.

I spent a lot of time observing the contributions made by different delegations and how other groups in the room responded to them, especially on the topics that are currently very sensitive: Ukraine and Gaza. While many of the contributions seemed fairly performative, I was listening out for the unscripted moments: extra comments that were made, facial expressions, emotional moments, use of silence, inflection of the voice.

IH: We are not often in the position to sponsor multiple researchers to attend international events. None of our team had been able to attend the first event in this series, held in Morocco in 2023, and it made a kind of sense to support a diverse set of scholars to attend and feed back on the second iteration—especially noting you were each able to secure additional sponsorship.

What would you say was the benefit for you of attending? Did you make new connections? To what extent do you feel that this kind of opportunity positions you as an ambassador for Cambridge researchers?

AU: Attending the event was valuable on multiple levels. Intellectually, it gave me space to reflect on how my research might speak to international contexts and real-world policy debates. I especially appreciated the smaller panels, such as the session on Women in Public Life, which focused on interfaith dialogue and the inclusion of women in political and religious spheres. The conversation there felt honest and impactful. I connected with several panellists, including those from the Women’s Faith Forum, who have since invited me to join their mailing list and explore future collaborations.

I also met Professor Ahmed Shaheed, a Professor of International Human Rights Law in the School of Law and Human Rights Centre at the University of Essex. He directs a Human Rights Centre Religion and Equality project, Mobilising a global alliance to counter Islamophobia, and we’ve been in discussions about potentially working together. These kinds of connections go beyond networking, they offer opportunities to expand my research and impact beyond the academy.

In terms of being an ambassador for Cambridge researchers, my presence contributed to a more diverse and critical academic voice, especially as someone working on Islamophobia, gendered trauma, and interfaith engagement. It also allowed me to think more creatively about how I might bridge academia and public life in my next steps.

VPE: I think it was immensely valuable to have a variety of disciplines from Cambridge represented, as well as three scholars who specialize in different faith traditions—I was able to meet quite a few Parliamentarians, NGO actors and even some of the other academics who attended. I made contact with Parliamentarians from Canada, Chile, Morocco, Algeria, Ireland among others. I stayed in the plenary meetings throughout, and was able to see how the choreographies between the different guests actually presented themselves while smaller groups met simultaneously to have more interactive discussions.

I also met the director of the interfaith church in Brussels (EU) which puts on concerts for peace and is interested in some sort of proposal, and a Parliamentarian in Canada who could be instrumental for a project I am collaborating on with a collection of Jewish Moroccan Canadian material that is led by an academic in Canada. These are just two examples of possible future steps stemming directly from the meeting.

MvdT: I had an opportunity to address the plenary session and say a few words about the role of Parliaments in democratic backsliding, as well as the rise of Christian nationalism. I wanted to say a few words about Christians writing the black pages of the history books and the responsibility that traditions have for their successes and their failures. Whereas I usually enjoy the safety of the written word, it was exciting to speak about this in a Parliamentary setting. It helped me to think where else I might speak rather than write.

IH: I’m conscious the pattern of your own research takes you to different conversations and spaces. Setting aside the peculiarities of a Parliament, I’d be interested to hear you each reflect on the value of international spaces, whether in relation to the Rome experience or more generally.

What is the value of engaging across national boundaries?

AU: International spaces like this are great for comparative thinking and for breaking out of local or national silos. My PhD research focused on Muslim women in Britain, but I’m increasingly interested in how women experience public life and safety across different global contexts, particularly in areas where political or religious tensions are prominent. Events like this allow for a kind of intellectual cross-pollination, where experiences from Ethiopia, Morocco, or Indonesia can shed light on challenges and possible solutions in Western contexts too.

Global engagement also helps reveal the structural commonalities behind religious exclusion, such as nationalism, misogyny, or populism, which manifest differently but resonate across settings.

VPE: I often engage across international boundaries in my work, but the fact that this was an international political encounter was what made being present so incredibly valuable. I often see the results of the decisions that are made by these meetings, or organisms, but without having had the conversations with the decisionmakers. Understanding their comprehension of the mechanisms available to them for the sort of desired impact which will create a real-world effect was eye opening, and will provide me with pathways to propose mechanisms that they may not have thought of.

The key issue here will be to stay in communication. I aim to attend the next meeting in order to continue building those relationships towards the future.

MvdT: A place like this fulfills many functions, most of which we won’t have seen. It provides a fruitful space for encounter and I enjoyed how many relevant people I got to know in just a few days. Some of these will lead to joint events and collaborations, some of these will remain useful connections for a later day.

IH: And in terms of the substance of the discussions you witnessed and participated in, what concerns came to the fore? Is there anything you would have wished to hear more of? Or less?

AU: One observation I had was that some of the plenary sessions and formal ceremonies leaned more toward self-congratulatory accounts of national progress, there was a lot of emphasis on what countries were doing “well,” and less time for critical reflection or debate. These segments sometimes felt performative rather than substantive. By contrast, the smaller, more focused panels were far more engaging.

For example, in the Women in Public Life session, we heard a compelling story about a young man in Ethiopia who had supplied weapons but changed course after interfaith engagement—a concrete and moving example of dialogue in action.

I also felt that conversations around Palestine and Israel were somewhat muted at first. Although they surfaced more explicitly in later panels, early references were vague or couched in generalised language about “global tensions” or “conflict in the Middle East”. Given the urgency of the humanitarian crisis, it felt like a missed opportunity not to foreground that issue from the outset.

VPE: There was repeated concern from the leadership that these conversations not stay as ideas and platitudes, but that they lead to real proposals and actions. I also noted that most of the public speakers were reluctant to address problematic issues within their own countries. There was a general environment of performativity and national isolation. I found that the academics and members of the NGOs (particularly) were more forthright in honest communication publicly and connecting afterwards.

I was amazed that even though this was occurring during the war between Iran and Israel there was no direct mention of that, and even though there were some Israeli and Palestinian attendees that presented via video-conference, to my knowledge none of the Iranians did.

In part this was because there were faith representatives from certain countries that actually live elsewhere (in London, for example) which seemed to diminish the true international aspect of the conversation.

MvdT: What stood out to me is how certain topics are really important to some and perhaps less so to others. We live in a time when people are comfortable enough speaking their own truths (and speak them loudly). However, “being right” is not enough to build coalitions in support of what one believes to be right. It is important to be able to reach out to those who might disagree with you, or who might prioritise certain issues differently.

IH: The logistical burden of organising such events is not negligible. To what extent does the “ownership” or “sponsorship” of such spaces impact what is possible or imaginable?

AU: The nature of who owns or sponsors these spaces inevitably shapes the narrative, tone, and agenda. When events are hosted or funded by governments or intergovernmental bodies, there can be an implicit pressure to focus on diplomatic success stories, rather than uncomfortable truths. This can create limits around critique, particularly on sensitive issues like Palestine, minority rights abuses, or religious discrimination within host nations.

At the same time, sponsorship by respected institutions does lend credibility and visibility, especially to marginalised voices. The challenge is to maintain intellectual independence and ensure space is carved out for grassroots voices and lived experience, not just official talking points.

VPE: In part the space, its architecture, the history, how grand and elegant it is meant that attendees felt a sort of gravitas to their participation. Additionally the fact that it was in Rome during the Jubilee year and that we had a meeting with the Pope (and that certain of the attendees met with the Pope that week in small numbers) meant that there was a sense of excitement about the historic and global nature of the gathering.

I think that these elements can become inspirational for the people in attendance, permitting them/us to feel that our contribution may be much larger and more impactful than we might perceive it to be from our usual vantage point.

MvdT: This particular iteration of the conference was hosted by the Italian Parliament. While this did not translate into particular visibility during the conference, it became rather apparent during the papal audience, when there were suddenly a lot more Italians around and even Giorgia Meloni turned up!

As for me, I was pleased to pass on a copy of “The Global Sourcebook in Protestant Political Thought” as a gift to Pope Leo—part of me hopes it’s somewhere in his office now.