A new exhibition is opening at Manchester Jewish Museum this month, exploring the legacy of Rabbi Moses ben Maimon, aka Maimonides.

Maimonides from Scratch began as an interdisciplinary effort to explore Jewish and Muslim presence and place in Manchester and Marseille through creative practices. The team come from backgrounds in art, anthropology, literature and religious studies. Over the last couple of years, through workshops at the Manchester Jewish Museum, in schools, and at the Marseille city museum, the team has developed a stop-motion film about the life of Maimonides, scholar, physician, philosopher and community leader. Though more than 800 years have passed since his death (1204), Maimonides’ work continues to resonate in and beyond Jewish spaces.

CIP Programme Manager Dr Iona Hine caught up with colleague Dr Anastasia Badder to learn more about the Maimonides from Scratch project and the University of Cambridge’s contributions. The following represents a lightly-edited extract from their conversation.

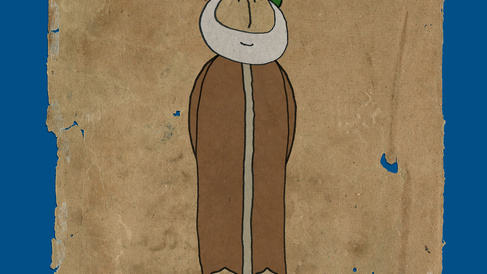

Maimonides from Scratch exhibition poster, Manchester Jewish Museum 2026.

Iona: The exhibition poster [shown above] looks like a manuscript page with a small cartoonesque figure, a pen sketch, which I assume is there to represent Maimonides. There’s also something scribbled at the top?

Anastasia: The poster features our animated vision of the RaMBaM, the Hebrew acronym for “Rabbi Moses son of Maimon”. “Maimonides” is the Greek version of his name.

These different ways of naming him speak to the different realms and spaces and linguistic traditions that Maimonides himself moved through.

At the top, in Maimonides’ own handwriting, is his signature saying “Moshe” (Moses), scrawled in a copy of a book that he once owned. The book fell apart and pages from it were deposited in the Cairo Genizah, alongside many of his other drafts and correspondence. [Editor: Read on to see the full signature in a sample animation below, as words lift off the page.]

In fact, we started the entire project with a hands-on introduction to the Taylor-Schechter Cairo Genizah fragments now held in Cambridge University Library. These fragments were ritually stored away in medieval Cairo out of respect for writings that may contain the divine name.

Holding these ancient fragments proved to be a really moving encounter. These materials really pull on people. They evoke all kinds of feelings and ideas and personal memories as well. They also spark new ideas, which we really saw in our discussions that followed as we started to develop ideas for the film.

Iona: So how did you go about animating Maimonides? What information do we have about what he looked like?

Anastasia: There are quite a few statues and coins and so on with his image, but we actually don’t know what he looked like. All the images you might see of him are artists’ renderings of how they think he looked.

We wanted our animated Maimonides to be simple, impactful, and respectful. So we spent a lot of time thinking about the style, about what he might wear, his clothes and so on. We discussed his appearance with the students involved and with the Manchester Jewish Museum volunteers involved in the project. They had lots of ideas about really the details of his appearance, whether he should wear shoes, what those should look like, his beard and so on, all of which we took into account. The poster has the final product of that discussion.

Storyboarding Maimonides— photograph by Dr Anastasia Badder (2025)

Iona: How did the schoolchildren relate to Maimonides?

Anastasia: A lot of the students and museum volunteers knew about Maimonides before this project and some knew quite a lot. Working with young students was really important and, for me and for the team, the most exciting element of this project.

The children—maybe more so than some of the older museum volunteers we also worked with—really felt free to explore Maimonides. They weren’t embarrassed to draw, to get super creative and imaginative, to try out new ideas or possibilities across the development process, and to think about Maimonides in new ways.

The intergenerational aspect of this work also made us think about notions of transmission that permeate both Judaism and the work of Maimonides himself. Some of my previous work has been on Jewish learning and education and transmission. It was essential for us to engage with young people and to have this transmission element—this intergenerational element—in our work.

We worked with a school in Manchester and one in Marseille—though I was not able to participate in person in Marseille due to the unexpectedly early arrival of my baby son!

The students were involved at every step of the process, from ideas to storyboards, to the overarching theme of the animated film that we produced, “Maimonides the Healer”. The film is the centrepiece of the Manchester exhibition. Throughout, we shared drafts with the students and made changes to those in response to their questions. We listened to what was meaningful to them, and what jumped out at them.

Iona: Can you tell us about the process of creating a storyboard?

Anastasia: Creating storyboards is a hands-on process. You have to divide up your narrative into very tight, succinct scenes to create the board. The participants had to think about what story they wanted to tell about Maimonides, choosing six or seven key details that they wanted to get across. They had to dig into those details about Maimonides that they felt were most important. Eventually, narratives started to take shape.

Iona: And how did you move from storyboard to film?

Anastasia: Stop-motion animation is a technique where a filmmaker works with physical objects, moves them incrementally and takes a photograph with each movement. When the photos are all played in a row, it looks like the objects are moving on their own. It takes tons of photographs to produce a short animation. Hundreds of photos might be a few seconds of film. This is a wonderfully absorptive process where you’re guided, constrained, and sometimes freed up by the objects you’re working with and what they can do and what they can’t.

Very often, when you’re creating a stop-motion film, you might start with a plan, but as you go along, as you start working with your objects, you’re led somewhere else. New ideas emerge in response to what’s going on with the object. It’s an exciting process and it gave students in the Maimonides from Scratch project another route for exploring themes from Maimonides work and life.

In the first workshop, they used fruit to think about ideas of movement and encounter from Maimonides life. Fruit is a really exciting material for kind of thinking about these themes in particular. They’re different textures inside and out. And the different ways we can slice, peel, mash them, and carve them produce different effects and might lead us to new ideas or different insights.

In the second workshop, participants worked with textiles to think a bit about text and also about the act of weaving together. The metaphor of weaving is useful in thinking about the many cultures and languages across Maimonides’ life.

Please allow social and marketing cookies to show embedded content.

Iona: So what are visitors going to discover when they go to the exhibition in Manchester? And what learning are you hoping that people will take away?

Anastasia: Visitors will see behind-the-scenes pieces from across the project, such as sketches made in the process of designing Maimonides, the storyboards created along the way, and some photos of the project in action. We also hope that they’ll get a sense of the way this project weaves together the anthropological, the museological and the pedagogical.

Of course, visitors will also get to see the stop-motion film: Maimonides the Healer, which will premiere at the exhibition launch on 11th February 2026 and will only be available in the Manchester Jewish Museum until June of this year. They’ll also get to see some of the Genizah fragments actually that inspired this work or got this work started, and even get to try their hand at copying some of Maimonides’ glossary of Judaeo-Arabic into Judaeo-Romance, with a really exciting and recently discovered Genizah fragment that I think speaks to these themes of encounter and translation that we thinking about across this project.

I hope what they’ll take away is this idea that there have been and will be many Maimonides. Maimonides has been and will be different things to different people, in different contexts and we can think about how and why that is, and also how these different Maimonides might resonate with each other, speak to each other and what that means for the people to whom he’s an important figure.

For people who want to see and learn more about the Cairo Genizah fragments, it’s also possible to visit them at Cambridge University Library.

Iona: And what is next for the Maimonides from Scratch team?

Anastasia: We are planning to continue the project. We are organising another From Scratch workshop series, this time in Morocco, which will be especially exciting because Maimonides and his family spent several years there in Fez in Morocco after they left Cordoba and Spain. There will also be further outputs from our workshops in Marseille, so keep an eye on that space!

I’ll be booking my journey to Manchester. Anastasia, thank you for taking the time to tell me about the exhibition. I hope the launch on 11th February is a great success!

Some key details

Anoushka-Alexander Rose, Anastasia Badder, Eliaou Balouka, Sami Everett, Odélia Kammoun, Sonya Nevin and Steve Simons are researchers from the University of Southampton (Parkes Institute for the Study of Jewish/non-Jewish Relations and Winchester School of Art), the University of Cambridge, and Birkbeck, University of London. In addition to input from Melonie Schmierer-Lee (Genizah Research Unit, Cambridge), the project has received funding and/or support from the UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council, the Panoply Vase Animation Project and King David Primary School.

The video snippet included above was provided by the Panoply Vase Animation team. Additional thanks is due to Melonie for editing the above interview.

Dr Badder’s previous work with stop-motion animation includes a classroom pilot for religious education in Key Stages 2 & 3. Her anthropological research on how attention is directed within part-time Jewish education programmes resulted in the Journal of Jewish Education’s best article in 2024, Knowing which way to turn. (See links below.)

Planning a visit to Manchester Jewish Museum? Maimonides from Scratch will be on show from 11 February to 24 June 2026. You’ll find more information about the exhibition and visitor arrangements at their website, manchesterjewishmuseum.com.